The first games I developed were for a British computer system produced by the ubiquitous (if you’re British, anyway) Amstrad plc: the Amstrad CPC-464. The games were “Manic Miner” and “Jet Set Willy“, both “ports” from the original Sinclair Spectrum versions.

I spent the latter half of 1983 unemployed after leaving my Electronics & Electrical Engineering studies at Manchester University two years in. I was putting the Z80 programming I’d learned at college to use, attempting to create machine language games on the Spectrum.

I originally obtained the machine to pursue my interest in electronic music, as it was easy to cobble various hardware bits onto the expansion port. Still, the availability of games for the system was too tempting. Inevitably, I ended up spending more time playing and disassembling them, and then trying to make a game of my own.

I burned many, many midnight hours poking away at the “dead flesh” keyboard. I would load the OCP assembler and source code from cassette tape, only to watch it all die horribly in a spectacular sequence of rainbow attributes, black screen, white screen…

Copyright 1982 Sinclair Research, Ltd,

…rinse, repeat.

Actually, the “rainbow” attributes were mostly imaginary since I was using a black and white TV. I made only occasional incursions into the living room, armed with the computer, power supply, cassette deck, and cables, to see how things looked on the family color set. This was much to the chagrin of other family members who quite rightly expected to watch TV rather than my experiments in abstract, attribute-powered modern art.

My mother was my very generous benefactor, procuring the Spectrum computer and the TV when I did not have the financial wherewithal to do so myself. Not that cash was exactly a bountiful resource for the family at the time. I am eternally grateful to my Mum for this, without her help my career may have taken an entirely different direction.

By early 1984, I’d put enough of a “demo” (a sideways scrolling platform game) together to persuade Software Projects in Woolton Village, Liverpool, to hire me as a programmer. So, in March 1984, at the ripe old age of 20, I moved from my mother’s house in Barnsley, South Yorkshire (which I had gratefully used as my base after discontinuing my studies) to sunny Birkenhead on the Wirral (a contentious geographical description, perhaps) where I set up residence in a terraced two-bedroom house on Holt Road belonging to Alan Maton, the Managing Director of Software Projects.

Incidentally, Software Projects was based in portions of what was the Bear Brand Complex, where the Bear Brand Tights were manufactured. The Bear Brand was demolished in 1997, making way for a Tesco Supermarket.

|

| Tesco on Allerton Road is on the site of the old Bear Brand Complex |

Once installed in Merseyside, I started to focus on the job at hand. We spent a deal of time looking at the MSX system (which was going to be the “next big thing” – I always thought of it as basically a Z80-based C64) and the Tatung Einstein (failure as a consumer electronics product, later quite popular as a development system). I also recall looking at a Memotech system. Nothing very productive really happened during this initial period. However, I did benefit from getting to know Derrick Rowson (who would be my programming partner in crime on the CPC games). Derrick had written a tiny monitor/disassembler (an exercise in self-modifying code and part of my Spectrum toolkit for years to come) and was quite a brilliant programmer.

The thing is, nobody was really managing us, so we were pretty much left alone to just get on with things: the net result was no net result. I remember asking for development tools (an assembler, documentation) for the MSX machine for a long while (we had a consumer version of the Japanese machine, a Yamaha, if I recall correctly, with Japanese manuals, etc.). In 1984, you couldn’t just Google it. I was informed by the owner of SP, Tommy Barton (rest in peace, Tommy), that “his contacts @ Hudsonsoft” (never did get to the bottom of that one) were adamant that no further documentation or tools beyond BASIC on ROM were needed and that my requests for tools were, in fact, a smokescreen designed by me to cover up the fact that I really didn’t know what I was doing.

At one point, I was summoned to Tommy’s wood-paneled office and told that I was on the chopping block because I hadn’t produced anything and kept making excuses about needing tools. I had, he insisted, obviously lied about writing the demo I’d used to get the job in the first place.

Tommy, “The cavemen didn’t need paintbrushes.”

Indignant programmer (not I, alas), “Yep, but they needed paint.”

So, clinging onto my job by the skin of my teeth, it was probably my saving grace that the Amstrad CPC was announced around this time. Here was a capable machine with a real keyboard, tools, and documentation. And it was Z80-based, which meant that SP’s cash cows, Manic Miner and Jet Set Willy, could be ported feasibly and predictably. Paint, at last.

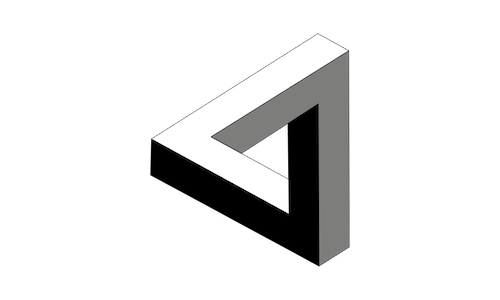

Manic Miner

|

| Manic Miner on the Amstrad CPC-464 |

This was pretty much a direct port from the Spectrum version. It ran in the 4-color mode, which meant that not all the 320×200 display area was used (the Spectrum is 256×192). Each screen in the game was given its own 4-color palette. Interesting trade-off given that the spectrum essentially has 15 colors (bright black being the same as black), albeit that only 2 can be used in a given 8×8 pixel block, and even then, both colors are either “bright” or not. We did some tricks with the raster interrupts that allowed us to use a different color palette for the status area at the bottom of the screen, reducing the monochromatic look to some extent. It came out pretty well overall and played pretty much identically to the Spectrum original. If I remember correctly, though, the “port” was carried out without access to the original source code; we had to reverse-engineer the game (not an unusual situation back then, to be fair). Derrick’s disassembler/monitor to the rescue!

Matthew Smith, the (very talented) originator of Manic Miner and JSW made only relatively rare appearances and had little involvement in the CPC versions. To me, he seemed shrouded in mystery, though that’s probably because I was somewhat in awe of him. Manic Miner (along with the early Ultimate games) was the main reason I pursued a career in the industry. Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy, Atic Atac, and Lunar Jetman (I never did find the trailer, though) are all burned indelibly into my memory. Matthew was something of a hero to me.

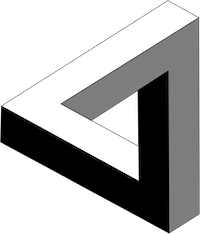

Jet Set Willy

|

| Jet Set Willy: The Final Frontier on the Amstrad CPC-464 |

Next, Derrick and I started work on Jet Set Willy. Again, the original source code was not provided. We used the same 4-color 320×200 screen resolution, but this time, we were feeling ambitious and decided to add a bunch of extra rooms over the original game’s 60 or so. We ended up with 132 screens – the frustrated game designer in me being allowed to surface.

Which is an interesting point. Back then (in the UK at least), there really was no such thing as a “game designer” (although the ill-fated Imagine Software may have attempted to define the role more). I think the industry just about had the notion of “pixel artist”, though that was a stretch.

Games of the day were often designed, programmed, and graphics created by a single person – Manic Miner & Jet Set Willy being great examples. Pixel artists were few and far between. The art tools of the day were so cryptic that you were at a distinct disadvantage as an artist if you were not also a programmer (mainly because the tools were created by the same programmers…). A few would-be programmers went on to become pixel pushers. Producers were yet to be invented. How things have changed!

Back to JSW. There is a detailed breakdown of the additional rooms we created at Julian Wiseman’s site, including commentary from Derrick and myself. We added quite a bit to the game beyond simple room additions; too much to detail here, but the article linked above on Julian’s site covers those additions pretty well.

Derrick made an editor, and we shared the effort to create the new rooms. Several new rooms contained sprites I had previously created for the demo I’d originally sent to SP. I modified Willy, adding the space helmet, for the new Starship Enterprise “space” levels we added. I wrote the music driver and ripped the C64 song data for the Moonlight Sonata menu music, and I composed the in-game music (sorry …) on my trusty Casio MT30 (which was later stolen from the Holt Road digs during one of several break-ins).

|

| Some of the sprites I created for Jet Set Willy CPC-464 |

One of the rooms we added to the CPC version of JSW was called the “Cartography Room”. This room lit a collidable square for every other room you visited, forming an (almost) complete map of the game as you visited each room. This also allowed you to reach certain unreachable objects in that room – a cute little feature. Most people do not know that if you enter the super-secret cheat code, this room becomes a fully functional room selector cheat, where you can, using a cursor, select the room you want to go to, press the fire button, and go straight there. Nice debugging feature, never revealed, so far as I know.

The cheat involved typing the string “EMMRAIDNAPRRRTT” once in the game, with a couple of terminating characters for good measure. I can’t really explain the sequence – Derrick came up with it – I think it’s a kid’s eeny-meeny nonsense rhyme (at least, that’s what Derrick told me) along the lines of, Eeny Meeny Macka Racka, Air I Dominacka, Alla Packa Rumpa Racka, Rum Tum Tush.

By the time we’d finished JSW, our development environment had progressed to the point where we used a (shock) separate development system (we were using Tandy TRS-80 model 4 systems). Derrick even had a hard disk drive (5MB). It was nice to have a development environment like this (a sign of things to come), especially when compared to loading tools and source code from cassette tape. Honestly, though, I did just as much development at home on my CPC-464, with the monochrome green monitor and external 3” disk drive. Still, things had come a long way in terms of development tools in a short time.

Manic Miner & Jet Set Willy for the Amstrad CPC both shipped while I was 21 years old.

While at SP, I had become friends with a couple of other reprobates, Stuart “Stoo” Fotheringham, and Marc “Wonga” Dawson (now Marc Wilding). Actually, Wonga was the name of Marc’s budgie (who died in mysterious circumstances – a whole other story), but Marc used the name as a programming pseudonym for a while. Stoo was a budding C64 programmer who interviewed at Software Projects the same day I did. I have vivid memories of the interview, thanks to Stoo, or at least the friend, let’s call him Fred, he’d brought along with him for the day (Stoo was only 16 at the time). Alan Maton took me, along with Stoo, Fred, and a software distributor whom Alan also met that day, to a local Woolton Village Chinese restaurant (the King Do) for lunch. Fred, who did not seem shy, was regaling us with a tale from his days working behind the counter of a computer store. The story culminated with a very inappropriate line, delivered with gusto, just as the demure female restaurant server placed Fred’s meal in front of him. Glances were exchanged, and I thought this had blown the interview for Stoo, but needless to say, Stoo got the job. He quickly switched from programmer to pixel pusher (he was a much better artist, and his art benefited from his technical know-how).

Marc was a C64 programmer and came to SP from Imagine Software after their collapse. Marc had just finished BC Bill on C64 and was working on Imagine’s so-called Mega Games up until their collapse.

|

| Print ad from 1984 taken outside Liverpool ABC Cinema. Stoo and I both appear. |

After a while, Stoo and Marc left to join a new Liverpool-based company, Odin Computer Graphics. Odin was run by the same people behind Thor Software, who had produced the Jack and the Beanstalk games. Odin was a stab at the higher quality (price point) end of the market.

After finishing the CPC version of Jet Set Willy, I left Software Projects to work at Odin with Marc and Stoo. Derrick Rowson stayed at SP and went on to port our CPC version of JSW back to the Spectrum, where it was released (very much to my surprise) as Jet Set Willy 2!

Read the first part of my Odin Computer Graphics recollections here.

See my Q&A with Retrogamer Magazine on Manic Miner for the Amstrad CPC.